Fentanyl test strips are in demand at Bay Area bars and restaurants: ‘People come in just for the strips’

Danielle Echeverria March 14, 2022, Updated: March 15

On a Thursday afternoon, Alison Heller arrived at Rockridge Improvement Club in Oakland right when it opened at 4 p.m. But she wasn’t there just for fun — she was coming in to refill the bar’s supply of fentanyl test strips.

“We just restocked yesterday, but I’m sure they need more,” Heller said, as she took the plastic lid off of the fishbowl in the bathroom. Sure enough, eight of the bowl’s 12 strips had already been taken. Heller promptly restuffed the bowl.

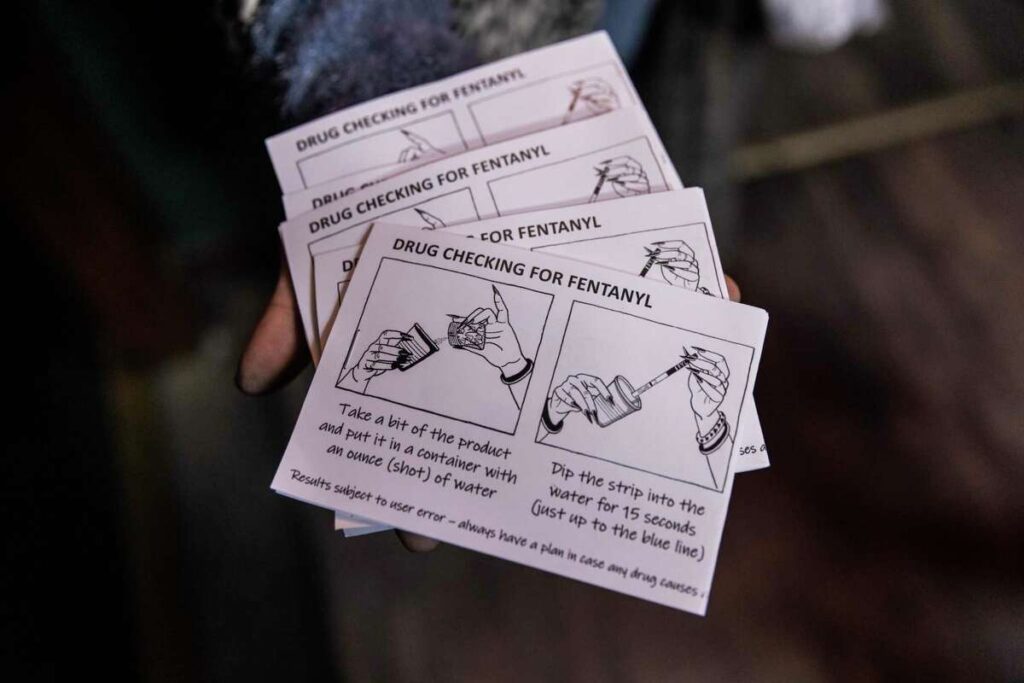

Heller is the co-founder of the nonprofit FentCheck, which orders fentanyl test strips from a Canada-based manufacturer, BTNX, and brings them into bars, restaurants and other venues in the Bay Area after adding easy-to-read, printed instructions to each strip and packaging them in a plastic fishbowl.

The test strips are one way that an increasing number of Bay Area business owners — primarily those of bars and restaurants, but even in places like art galleries and tattoo parlors — are responding to the fentanyl crisis. And many, having had the test strips since last summer or earlier, say that demand is brisk.

To use the strips, people take a tiny fraction of a drug, mix it with water and then dip the strip into the mixture and wait to see if it turns up positive for fentanyl. That way, people intending to use drugs that are not fentanyl, like cocaine or ecstasy, can test to see if it’s been cut with the dangerous opioid.

Scott Ayers, who owns Rockridge Improvement Club, said demand for the strips is higher than he’d thought it would be. His bar receives around 100 test strips a week, with restocks almost every other day.

“It’s crazy,” he said. “Some people come in just for the strips.”

FentCheck’s co-founders say the strips are one form of “harm reduction,” reducing the chance that a recreational user would overdose after unknowingly consuming fentanyl-laced drugs.

“People are going to experiment anyway,” Heller said, adding that testing their drugs gives them the opportunity to be safe. “Harm reduction is for everybody, and we’re targeting a demographic that doesn’t realize it’s for them.”

The demand for the strips comes amid an increasingly deadly drug overdose epidemic. In San Francisco, about 7 in 10 overdose deaths in the past two years have involved fentanyl.

But fentanyl was very rarely the sole drug found in the system of people who fatally overdosed, medical examiner data shows. And because fentanyl can be lethal in very tiny amounts, even the slightest cross-contamination — intentional or not — could have serious consequences.

Fentanyl test strips haven’t always been well-received. Heller and her FentCheck co-founder Dean Shold, who’s also the chief technology officer for the Alameda Health System, said that some worried that it was enabling and even encouraging drug use, a sticking point in debates around harm reduction as an approach to helping addicts.

For his part, Ayers said he “was a little shocked” to hear about some of his fellow bar owners keeping the fentanyl test strips in their venues — “it almost seems like you’re greenlighting it, in a way,” he said.

But like other business owners, Ayers, who’s worked in bars and as a musician for 25 years, ultimately decided that he might as well face the realities of drug use, especially recreational, in places like bars — something he said has “never been uncommon” in his years of experience.

Now, after having had FentCheck along with Narcan — the nasal spray that can reverse overdoses — in his bar for a few months, he says it’s “fantastic.”

“You don’t want someone to die in your bar, right?” he said, adding that he’s never had to use Narcan. “That’s much worse for business than anything else.”

Jason Lujick, who owns the Legionnaire on Telegraph, was all in with FentCheck when Heller told him about it casually one night when she was waiting at his bar to meet a date. His was one of the earliest bars to start keeping it, and he quickly told his friends in the industry that they should get on board.

“I’m a huge proponent,” he said. “It’s so low-cost, and it saves lives.”

The concept is catching on. Heller and Shold have taken FentCheck to New York, Philadelphia, San Diego, Portland and Reno, and they hope to continue expanding it, even into schools — UC Berkeley recently partnered with the nonprofit to make the strips available on its campus. The two pay for the test strips — which go for around a dollar each — themselves, relying on donations to keep the nonprofit afloat.

Many of the venues involved host fundraisers for FentCheck or provide a donation themselves, Heller said.

Lujick keeps his FentCheck, along with Narcan, at the end of the bar next to the water. That way, if anyone has questions — and they do, he said — they can easily ask the bartenders about it.

Like Ayers, Lujick emphasized that having the test strips available doesn’t mean he wants people doing drugs in his bar — one of the questions people frequently ask him when they see his FentCheck setup.

“No, I don’t want people doing cocaine, heroin or molly in my bar, but they’re going to,” he said. “If any business owner, bar, owner, restaurant or whatever thinks that people aren’t doing drugs in their business, they’re out of their minds.”

And he said he thinks that many people aren’t aware of just how dangerous their drugs might be.

“The biggest issue here in the last couple of years is that now everything’s laced with an opiate that is a hundred times stronger,” he said of fentanyl. “And people are dying left and right from it, and we have to do something to stop it.”

Business owners also said that, since keeping FentCheck strips, they’ve noticed that all kinds of customers are grabbing them, either to keep in their purse or pocket for later, or to use that night.

Melissa Meyers, who owns the Good Hop in Oakland, said that some people are surprised to see the strips in her “bright, light” venue.

“It’s just that concept that drugs lie in a darker world,” she said. “The reality is, your neighbor who’s clean-cut, and you would never think that they would do something like that, is doing that.”

Above all, she said, like the other business owners, she believes it’s important to give people the opportunity to be safe.

“It doesn’t hurt us to offer it,” Meyers said. “Nobody’s going to die because we’re offering the ability to check your drugs.”