The Story Behind ‘Caregiver: A Love Story’

Next Avenue April 2021

Author: Julie Pfitzinger

Physician Jessica Zitter’s new film about the last days of a woman's life puts a caregiving husband in the spotlight

An intimate look at the beauty of dying at home. This is what Dr. Jessica Zitter, a critical and palliative care specialist, believed she was planning to reveal by filming the final nine weeks in the life of Bambi Fass, 59.

However, a year later, Zitter, author of "Extreme Measures: A Better Path to the End of Life," viewed the film footage that had been captured during those last days and was struck by what was truly revealed: the story of Fass' husband, Rick Tash, then 63, who, in 2016, became his wife's primary caregiver as she was dying of cancer in their Oakland, Calif. home.

"As we [she and co-director Kevin Gordon] were editing what we'd shot, I could clearly see the immense burden of caregiving on Rick," Zitter said. "Rick's story became THE story." And that story became the film, "Caregiver: A Love Story," now available on Good Docs.

Prepared to Die

Although Fass had been a physician’s assistant at the public hospital where Zitter works, that’s not where they met. Rather, it was at their synagogue, where Fass sat four rows ahead of Zitter.

“Bambi had always been very open about her melanoma,” said Zitter, of the woman’s four-year treatment for her cancer, which eventually became metastatic. “And she finally came to the point where she was ready to step off what I call the ‘end-of-life conveyor belt.'”

Tash’s goal, he says in the film, was to give [Bambi] the best care I can give her.”

Zitter recalls a phone conversation when Fass, who was growing sicker, told Zitter she had had enough and wanted to die. At-home hospice arrived the following day, beginning the end-of-life journey Fass was prepared to take.

“Bambi really was a new person then,” says Zitter. “She was celebrating her life.”

In one of the film’s many poignant scenes, Fass’ two grown sons, having traveled from their homes in Israel to see their mother for the last time in person, are shown sitting on the bed with her, one strumming a guitar and the three of them fumbling a bit – and laughing a little as well – through the lyrics to Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven.”

Tash and Fass met on a dating website approximately three years prior to her death. Both were divorced and, at the time, Tash was living on the East Coast. Fass relays their love story at the beginning of the film:

“I knew the cancer was starting to take over. We weren’t engaged,” she recalled. “I told him this is your ‘Get Out of Jail Free’ card. The next weekend, he came out and pulled out a box. I didn’t even open up the box. I just fell into his arms and said ‘Yes.'” They were married not long after, and were together for two years before Fass’ condition worsened.

Tash’s goal, he says in the film, was “to give [Bambi] the best care I can give her.”

But as Zitter says, “I” is the operative word for someone caring for a loved one at home.

“There is no physical support. There are things you can’t entrust to others,” she said.

According to the National Alliance for Caregiving, 53 million non-professional caregivers are currently taking care of loved ones. And as Zitter points out, the pandemic has increased awareness of the monumental challenges they face.

“Statistics show that sixty percent of caregivers have full-time jobs and they are forced to take twice as many days off each year as their non-caregiving co-workers,” says Zitter. “About a quarter of them leave the workforce altogether.”

Due to the demands of caring for Fass, Tash quit his actuarial job and was forced to draw down his savings. And, as he reveals later in the film, the physical and emotional burden of caregiving for his wife — and her death — left him traumatized and unable to work for the first year without her.

Emotional and Physical Burdens

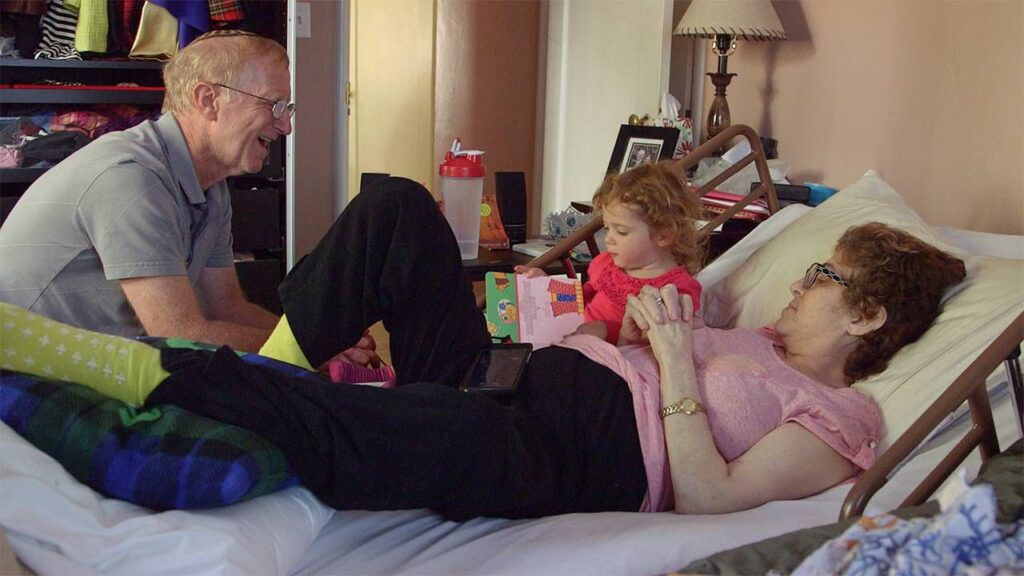

As Zitter spent time at the couple’s home, alongside a freelance camera crew she had hired to document the experience, she began to see the visible daily burden on Tash as he was caring not only for his new wife, but also for his three-year-old granddaughter Mya, who was living with the couple.

“In a keynote talk I’ve created to accompany ‘Caregiver,’ I talk about the myths of caregiving, and Number Three is ‘love can conquer all,'” Zitter said, making a reference to the romanticized view of caring for a dying spouse in the 1970 film “Love Story.”

“Rick was a newlywed, too, but he was living in the real world,” she continued.

As shown in the film, it was a world of monitoring medication, constant laundry and little or no time to leave their house. An aide came to the home three times per week, for 45 minutes; there was also an on-call nurse available, but other than that, the burden rested on Tash.

In addition to handling practical matters, Tash had to face the impending death of his wife.

“Her decline is more difficult than I expected,” he says in the film.

“My biggest goal is to raise awareness to a variety of audiences about what it really means to be a caregiver,” Zitter said.

And his own physical health suffered – there was a period of five days when Fass had to be transferred to a care facility while Tash, who felt guilty about the development, recuperated. When he was healthier, she returned to their home.

It’s not unusual for the health of caregivers to become precarious. Studies have shown that those caring for loved ones with Alzheimer’s have an increased risk for developing dementia. As many as 30% of those caregivers, according to Zitter, pre-decease the patient.

And for caregivers in general, their emotional and physical health can suffer resulting in anxiety, depression, cardiovascular problems and more.

“The average length of time that caregivers are taking care of a loved one is four-and-a-half years. Rick was caring for Bambi for nine weeks, and it took its toll,” Zitter said.

Raising Awareness About Caregiving

Zitter finished editing “Caregiver: A Love Story” in March 2020, just as options to host screenings, participate in conferences and approach film festivals started to disintegrate due to the pandemic.

“My biggest goal is to raise awareness to a variety of audiences about what it really means to be a caregiver,” Zitter said, adding that she’s reaching out to hospices, health care providers, caregiving groups and others about ways to screen the film. A link on the film’s website offers several viewing options for varied groups of all sizes.

As part of a curriculum she’s creating around the subject of family caregivers, Zitter recently showed the film to a group of medical students. When it ended, “at least half of them were crying,” she said, but at the same time, they were reflective about how understanding the burden of caregiving could be helpful in their own work.

“One of the students talked about a telehealth call she had just been on with a woman who had suffered a stroke. Her husband of forty years was on the call, too. The student admitted she never thought to ask him how he was doing, but now realized how his wife’s stroke would affect him,” explained Zitter.

For Zitter, who’s featured in the 2017 Academy Award nominated short documentary “Extremis,” available on Netflix and focused on her work with dying patients and their families in an emergency room setting in a Northern California hospital, portraying the intimacy of someone dying at home “lifts the veil.”

“You’re watching [Bambi] deteriorate, and you’re right at her bedside,” she says. “Seeing that may make some people reconsider their feelings about the experience of death.”

The Final Days

As the film progresses, Fass begins to fade away, growing more quiet. One of her goals was to live to see the birth of her granddaughter, Emunnah, in Israel, via Skype, which she does. And the day following a visit from her rabbi, Fass dies in her sleep.

As the film progresses, Fass begins to fade away, growing more quiet.

Another revelation Zitter had during the editing process, and in screening an initial cut of the film with a focus group, was that Tash’s story, after the death of his wife, needed some attention.

“I tend to be more interested in straight storytelling, but I realized we needed some final context around the impact of caregiving on Rick,” she said. “People who saw the film wanted to know what happened to him.”

In a scene shot two years later, Tash is seen driving Mya to school, passing her lunchbox back to her in the backseat of their car.

On camera, Tash says, “It was all about love. I have no regrets about marrying her. I would not lose that time for anything.”