100,000 Americans died of drug overdoses in 12 months during the pandemic

The Washington Post – November 2021

Author: Dan Keating and Lenny Bernstein

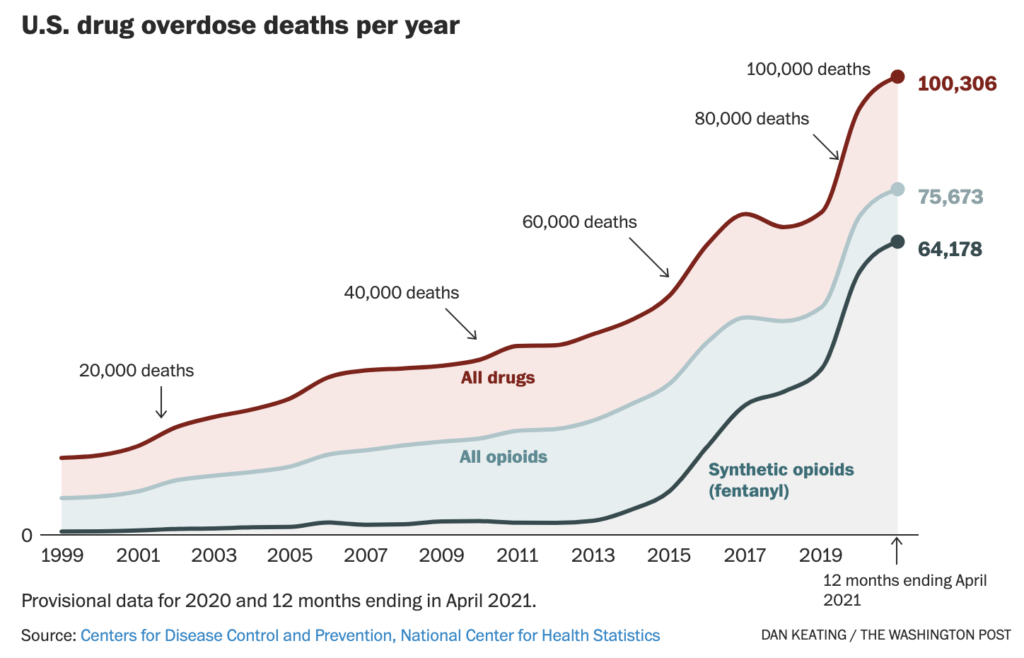

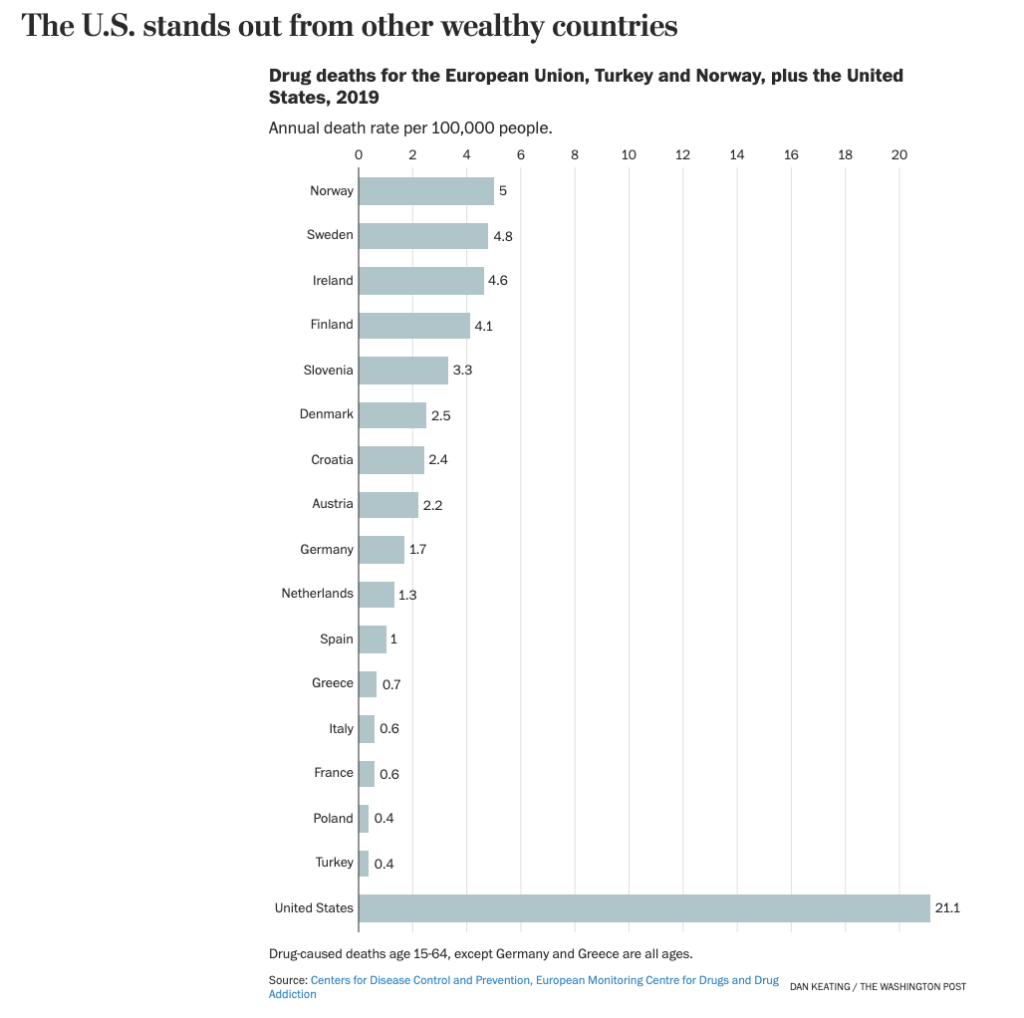

The U.S. drug epidemic reached another terrible milestone Wednesday when the government announced that more than 100,000 people had died of overdoses between April 2020 and April 2021. It is the first time that drug-related deaths have reached six figures in any 12-month period.

The people who died — 275 every day — would fill the stadium where the University of Alabama plays football. Together, they equal the population of Roanoke, Va.

The new data shows thereare now more overdose deaths from the illegal synthetic opioid fentanyl than there were overdose deaths from alldrugs in 2016.

Despite the efforts of governments, health-care providers, activists and others, the problem is growing much worse. The new figures, which are provisional but rarely change much in final tallies, represent a 28.5 percent increase from the same period a year earlier. The financial, social, mental health, housing and other difficulties of the covid-19 pandemic are widely blamed for much of the increase.

President Biden said in a statement on the overdose death data that “as we continue to make strides to defeat the COVID-19 pandemic, we cannot overlook this epidemic of loss, which has touched families and communities across the country.”

At a news conference Wednesday, other senior government officials acknowledged the increasing severity of the drug crisis, which has prompted the Biden administration to focus more effort on harm-reduction strategies. This approach includes trying to increase distribution of the overdose antidote naloxone and fentanyl test strips to users, to keep them alive while the government expands prevention and treatment programs.

But administration drug czar Rahul Gupta conceded that naloxone distribution is uneven across the country, depending on rules in different states. He offered a model law, suggesting some states could improve access to the drug by adopting it.

“Sadly … access to naloxone often depends a great deal on where you live,” Gupta, head of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, said at a news conference. Naloxone, he added, “must be made available to everyone who is at risk.”

Drug Enforcement Administration chief Anne Milgram noted a rise in fentanyl seizures, which she said have reached 12,000 pounds in 2021. That is enough to give every American “a lethal dose” of the powerful opioid, Milgram said. Increased use of methamphetamine is also a factor, she said.

The administration is asking Congress for $11 billion in the 2022 budget to fund anti-drug programs, which also emphasize prevention, treatment and recovery services. But little seems to be working at a time when an unprecedented drug crisis and a once-in-a-century viral pandemic are occurring simultaneously.

Fentanyl is many times more powerful than morphine, leading to more frequent fatal overdoses. It is increasingly laced into other drugs, such as cocaine, and counterfeit pills, killing some who consume it unknowingly.

During the worst of the pandemic, more users were alone, reducing the chances that other users or bystanders could call first responders in the event of an overdose, experts have said.

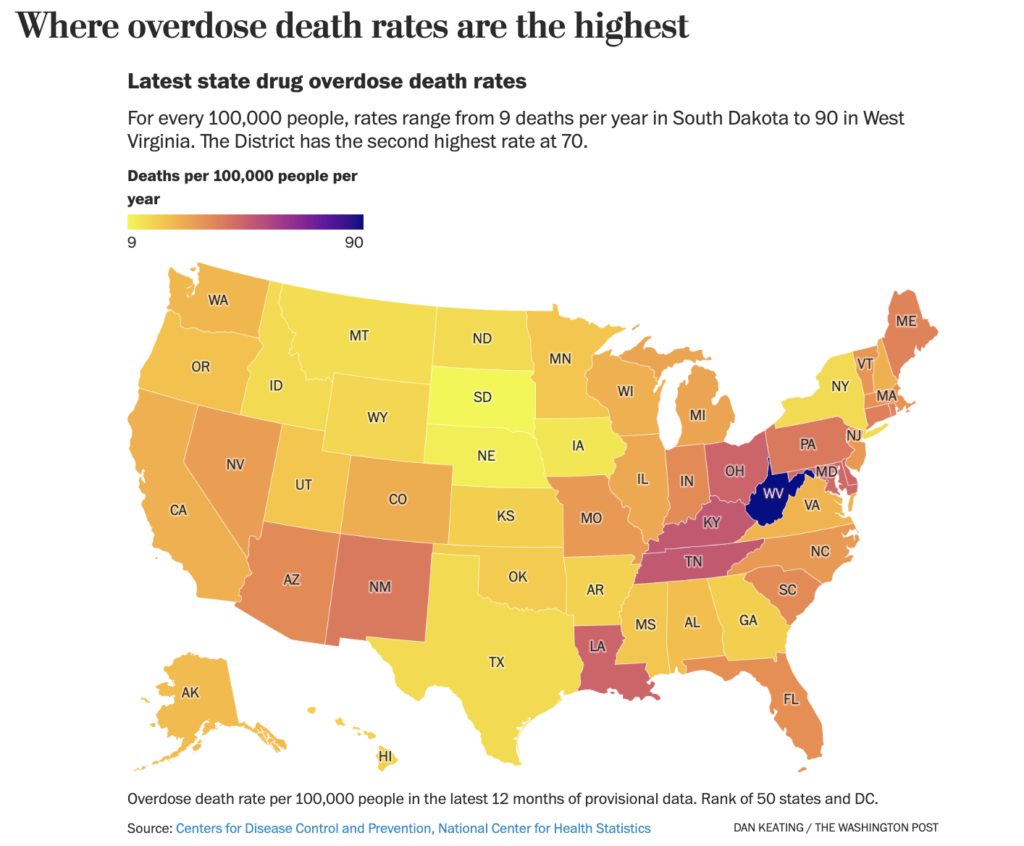

Overdose deaths are not evenly distributed across the United States. The worst of the crisis has shifted geographically over the past 20 years, as illegal users of pharmaceutical opioids turned to heroin and then illicit fentanyl. But Appalachia always has been hit hard.

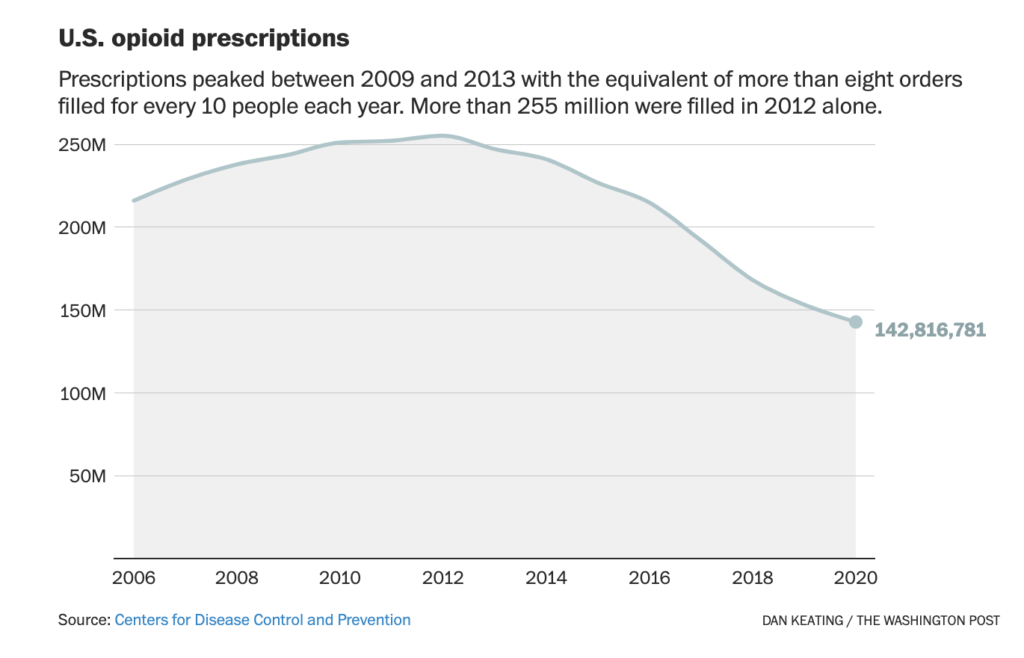

The number of opioid prescriptions issued by health-care providers has declined sharply as the crisis continues. Twenty years ago, doctors were aggressively treating pain as “the fifth vital sign.” Drug companies contributed to the idea that powerful painkillers could be used for a wide variety of ailments, not just cancer and end-of-life care. But as the addiction crisis ensued, physicians have cut back.

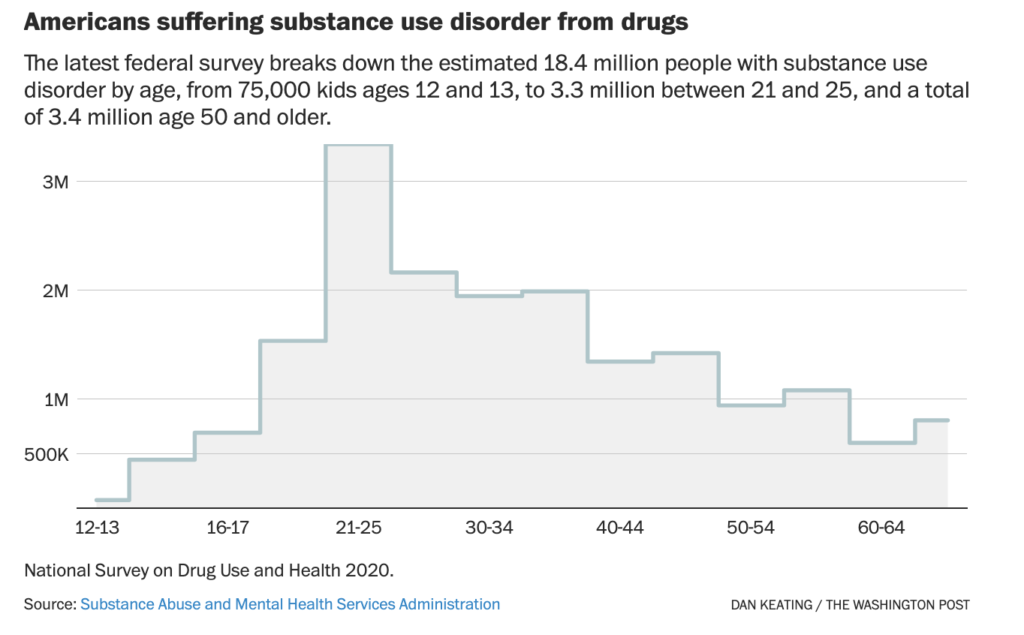

Addiction preys on young and middle-aged adults, who make up the bulk of those with drug-related substance use disorder. (Alcohol-related SUDs are not included in the chart below.)