Patients Drive Hours to ERs as Omicron Variant Overwhelms Rural Hospitals

Hospitals call staff with Covid-19 back to work to handle the surge of patients in parts of country strapped for workers

By Julie Wernau for the Wall Street Journal updated January 2022

When the Omicron surge hit the Navajo Nation this month, the main hospital that serves a far-flung and vulnerable population in the high desert across northern New Mexico and Arizona was immediately overwhelmed.

The 74-bed Gallup Indian Medical Center has so many patients that they are asking people, many of whom drove two hours for care, to go home and come back in a couple of days. “You’re not going to get a bed unless you need a ventilator, or you have a gunshot wound,” said William Porter, deputy director of operations at Team Rubicon, which sends volunteer military veterans to disaster areas. The group is deploying roughly 20 medical personnel to the Navajo Nation, home to approximately 173,000 people spread across 27,000 miles and three states.

The rise of the highly contagious Omicron variant is leading healthcare workers to take drastic measures to prevent breakdowns in care. Though Omicron may cause less severe disease than earlier variants, research has shown, infection rates far surpassing previous pandemic peaks have pushed up the tally of people experiencing severe cases of Covid-19. The U.S. this past week reached the highest recorded level of hospitalized patients with confirmed and suspected Covid-19 cases. In rural America, the problem is worse.

One or two missing workers can shut down an entire clinic. Now many are out sick with Omicron. Many rural facilities say they can’t afford to hire travel nurses at rates that have skyrocketed during the pandemic. And some clinics and family practices that typically provide care that can keep people from landing at hospitals are closing because Omicron has hobbled their workforces, too.

Rural hospitals are using veterans groups and foreign nurses to bolster staffing. Some are recruiting unvaccinated workers who were fired elsewhere for failing to comply with mandates to get the shots. And some hospitals are asking workers with Covid-19 to keep working.

“We really feel we have an impending medical crisis here,” said Teresa Tyson, nurse practitioner and executive director of the Health Wagon, a nonprofit clinic that provides free healthcare in Appalachian Virginia.

To keep people out of the hospital, the Health Wagon had been treating people with Covid-19 with monoclonal antibodies. Now they are rationing supplies of the treatment, making it more likely that some will need to be hospitalized, Ms. Tyson said.

“We’ve had to do this thing where we take this 78-year-old cancer patient over someone who is younger who we think can better weather Covid,” she said.

Sanford Health, a hospital system that serves remote parts of the Dakotas, Minnesota, and Iowa, started in late 2020 to recruit nurses from overseas to alleviate staffing constraints that worsened during the pandemic. Sanford’s goal is to convince upward of 700 nurses from countries including the Philippines, Nigeria, Brazil, and India to move by 2024. The system plans to pair them with staff who can help them navigate harsh winters and other peculiarities of life in the Dakotas. The first eight nurses are set to arrive in Fargo, N.D., sometime this quarter.

Sanford said hundreds of its 34,000 employees are out sick with Covid-19 and hundreds more are awaiting test results. One of the system’s critical-access hospitals has closed after all four of its nurses went out sick with Covid-19. Some patients are driving two or three hours to the nearest ER as a result. Sanford is considering cutting nonessential services and elective surgeries. It has asked asymptomatic and Covid-19-positive employees who no longer feel sick to return to work after five days.

“This is an urgent situation,” said Erica DeBoer, Sanford’s chief nursing officer.

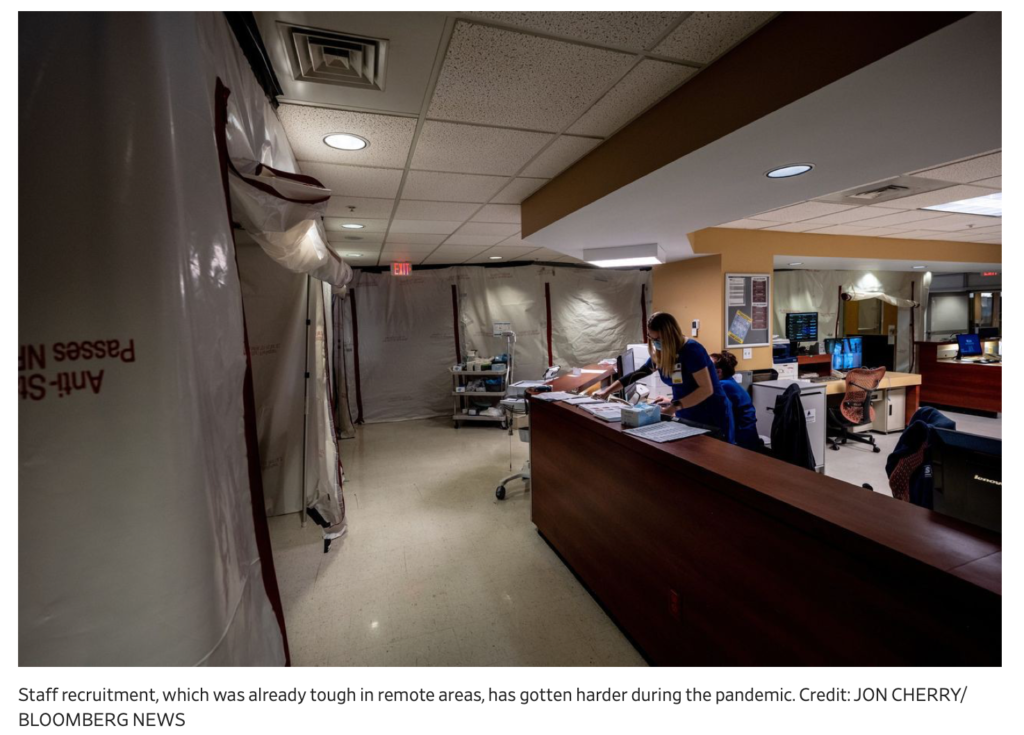

Recruitment, often tough for employers in remote regions, has gotten harder during the pandemic. Some recruiters are trying to draw nurses to remote areas for less money than they could make elsewhere by extolling the region’s natural beauty and the promise of recreation and adventure.

Justin Jacob, a recruiter at Uniti Med Partners and former ICU and ER travel nurse, recently placed a nurse in Sitka, Alaska, by saying that when he was nearly burned out, the state renewed his love for people and nursing. Mr. Jacob said he sold the nurse on moving there for fishing, hiking, whale watching, and crabbing.

Grant Studebaker, an assistant professor at the University of Tennessee and a family medicine doctor with West Tennessee Healthcare, said he arrived for rounds at a clinic recently to find the parking lot full of patients. The clinic in Jackson, Tenn., had switched from Covid-19 care during the Delta variant wave back to offering primary care, before returning to treating Covid-19 patients exclusively during the Omicron surge. Several staff were out sick, and the nursing supervisor was pitching in to run the lab.

“You know any pulmonologists by chance?” he asked. Several local pulmonologists have left or retired in recent years and haven’t been replaced, he said. General practitioners and medical residents now manage complex pulmonary problems and ICU patients, Dr. Studebaker said.

West Tennessee Healthcare is freeing up staff by having some patients monitor their own vitals remotely. It is also getting patients to conduct their own oxygen treatments.

“When that hospital gets strained, it puts a lot of people in this community in a really bad position,” said Leah Gilliam, a family medical doctor in nearby Lexington, Tenn.

Dr. Gilliam has been seeing patients with Covid-19 symptoms curbside during the Omicron wave out of fear that she could bring the virus home to her newborn. She said the influx of patients has been overwhelming. But for many, she’s the only option.

“If I turn them away, what am I going to do?” she said. “I don’t want them to go to the emergency department. They’re full.”