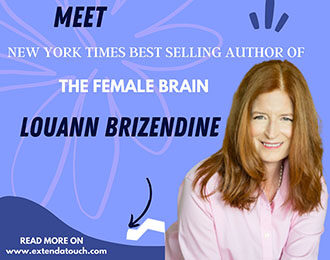

My Dad Died on 9/11 and His Body Was Never Found—Here’s How I’m Caring for My Mental Health 20 Years Later

By Cat Lafuente, September 08, 2021, updated March 8, 2022

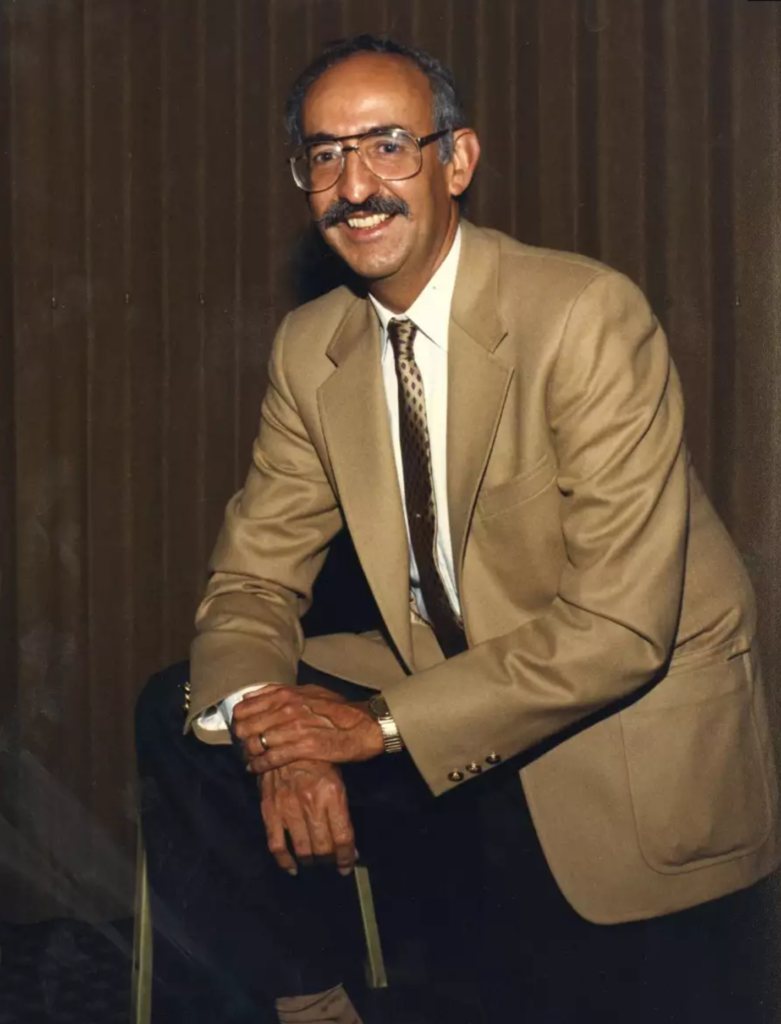

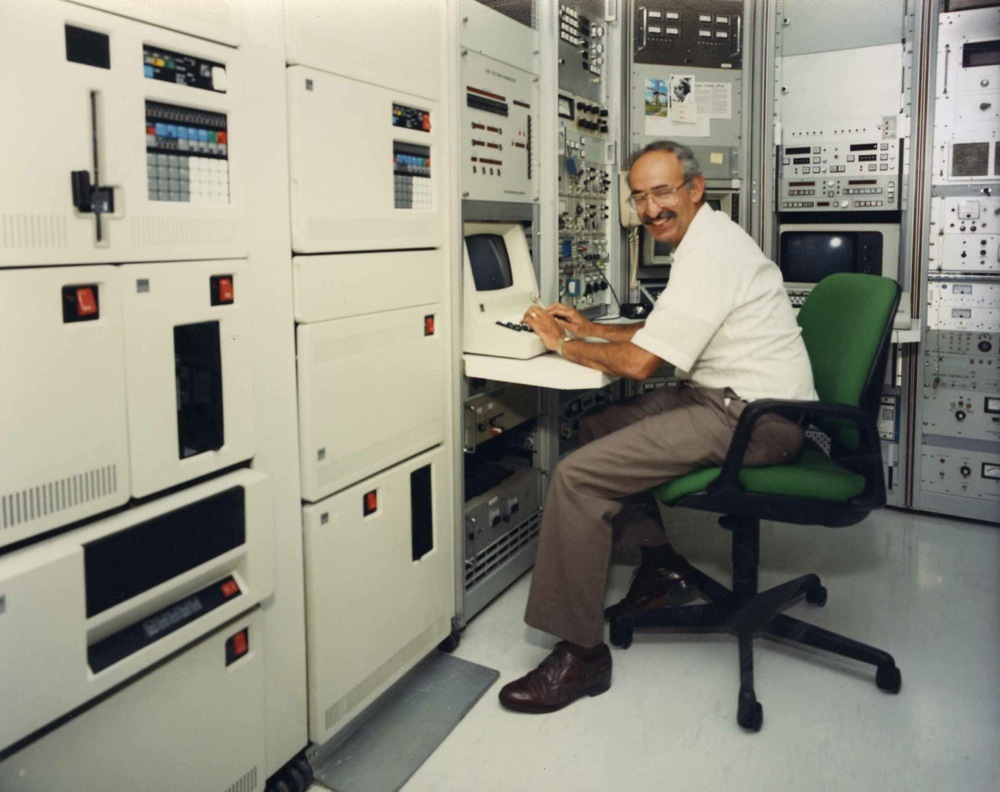

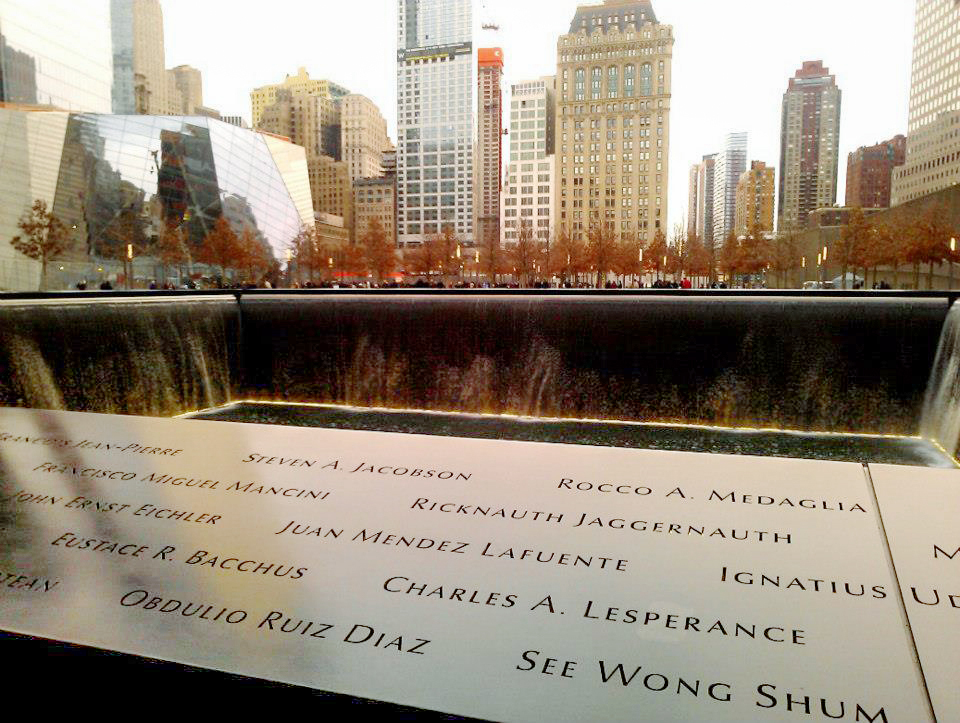

Juan Mendez Lafuente; Courtesy of 9/11 Living Memorial Project | CREDIT: COURTESY OF 9/11 LIVING MEMORIAL PROJECT

There is life after trauma, and it can be beautiful, even if it’s different from what you could have ever imagined before the worst happened. I’m living proof.

It’s hard to believe that it’s been 20 years since my father went missing on September 11, 2001. His last recorded activity was the swipe of his MetroCard at the 4-5-6 Subway in Manhattan at 8:06 a.m., on his way to the World Trade Center. After stitching together clues, we learned that my father was at Windows on the World—a complex on the top floors of the North Tower—when planes struck the Twin Towers. Like so many who were there, he didn’t make it out alive. And we never found a body.

Thus began a crash course in loss and grief in the aftermath of a terror attack that ripped apart so many families. I raced home from college—I’d just turned 21 the day before—to be with my family in Poughkeepsie, New York, as we searched for any trace of my father, who was a bank vice president. We called hospitals, we talked to people he commuted with, we laid flowers at the train station where he’d parked his car, we posted fliers like every family who was searching for someone after the attacks. The days of waiting turned into weeks, and then months.

Eventually, we came to accept the reality, a slow and inevitable realization no one wants to have. But we had to. In that time of waiting and anticipating the worst, I was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) by the mental health professional at my college. I couldn’t sleep, as negative thoughts were loud and persistent, and my anxiety kept me constantly anticipating the next bad thing to happen. It was like the whole world had been turned upside down, and suddenly everything that seemed important was a faint shadow of what it had been.

Even though it’s been two decades, I have had to care for my mental health every day since then. My anxiety and PTSD continue to be diagnoses I have to manage, lest I get lost in the deep sadness that lives inside of me—which I call the well of tears.

| CREDIT: COURTESY OF 9/11 LIVING MEMORIAL PROJECT

However, you didn’t have to lose a family member to be impacted by 9/11. “Most people can remember exactly what they were doing in the precise moment they learned what was happening,” Keith Young, a Maine-based certified clinical trauma professional and author of the book Trauma and Resilience: Your Questions Answered, tells Health. “Older generations would say the same thing about the assassination of JFK or the attack on Pearl Harbor.”

To that end—and especially in the wake of recent international events and with the 20th anniversary of the attacks upon us—you may find yourself once again dealing with triggers that exacerbate lingering depression, anxiety, and hopelessness. Fortunately, there are things you can do to hold on to your hard-fought peace. Here’s how I’m caring for my mental health 20 years after 9/11—and how you can too.

I’ve had to change what my concept of closure means

All relationships come to an end. Whether that ending is the result of a breakup, a conflict, or death, experts extol the virtues of getting closure, which looks different for different people. When it comes to death, closure often comes in the form of a funeral that commits a person’s remains to their final resting place—at least, that was my understanding before 9/11.

After 9/11, I had to re-define what closure meant to me because, while my family had a memorial service for my father, his body was never recovered. So closure became less about having a body and more about accepting absence. With nothing concrete other than his void in my life, that had to be enough for me to accept he was actually dead, as opposed to hoping he might come home (which I of course did anyway). That closure is a feeling I had to find on my own, because there’s no playbook for how to cope with the loss of a parent after a terrorist attack in which a body isn’t found.

Then there’s the lingering grief. “Grief isn’t so much a matter of achieving some defined state of ‘closure,'” explains Young. “A more fitting description might be that the grief changes shape over time as we learn to heal. It becomes less sharp around the edges. The pain remains in our hearts to some extent, and at the same time becomes a less constant and interruptive presence in daily life.” But it’s always there. In a way, knowing I will always grieve will serve as closure, as it’s a part of life now and it’s cemented into who I am as a person.

| CREDIT: COURTESY OF 9/11 LIVING MEMORIAL PROJECT

I don’t watch the news very often

This is very important: You don’t need to be informed about every single current event. There’s no moral obligation to be aware of everything going on in the world, and you’re not a bad person if you simply turn off the news or silence your phone’s news alerts. In fact, by doing so you are protecting your mental health. Watching the news can make you anxious. “Even if we’re not traumatized, the news can have a cumulative negative impact on our mental health,” Young shares. “It’s a steady dose of distress delivered to us each morning and night which, if left unchecked, weaves its way into influencing our worldviews.”

It’s good to be aware of the injustices going on in the world, but you have to protect yourself. That’s why I don’t watch the news very often, whether it’s 9/11 or otherwise. Even 20 years later I have to make sure to avoid triggers—like people tragically falling off of a plane in Kabul, as we recently saw—that take us all back to that horrific day. And while I want to be aware of the world’s horrors, I don’t always have the bandwidth for it, and that’s OK. I can always read about it later, which is far less traumatizing for me than live television coverage.

I take medication as an act of self-love

Immediately after 9/11, I started taking antidepressants and anti-anxiety medicine. Over the years I have tried almost every antidepressant out there, hoping that one would work without intolerable side effects. It took a lot of work to find the medication that helps me the most, but now that I have it right, I’m so grateful to myself for doing it.

It’s natural to be skeptical about medication, but don’t write it off completely, as the benefits are well-documented. “We deserve to take care of ourselves as attentively as we’d care for anyone that we love dearly,” Young affirms. “We’re equally worth the effort and sometimes need to remind ourselves of that.”

So trust me when I say it has changed my life for the better. My panic attacks—which are brought on by events that involve unwarranted cruelty, such as the harming innocent people—can be debilitating. But sometimes just knowing I can end them in a swift and healthy way calms me down in and of itself. We as Americans are taught to value doing things on our own, but tending to your mental health isn’t something to struggle with alone. Medication has helped me cultivate and maintain inner peace; maybe it’s something that you can consider talking about with your doctor, too.

I let myself off the hook from changing the world

In the years following 9/11, some very ugly xenophobia and racism reared up, and anti-Islamic sentiments became more prevalent than ever before. People have used 9/11 as a reason to hate Muslims and those of Middle Eastern descent, and I was really bothered by that. So I decided it would be my mission to help combat that ugliness. I got my master’s degree in religion (with a focus on Islamic studies), studied Arabic for four years, and lived in Jordan during the summer of 2011. I even enrolled in a doctoral program in the hopes of becoming an educated authority on Islam, convinced I could help others by doing so. The problem is that I wasn’t doing any of that for myself; I was doing it for others, and I thought it was what I should be doing. But I was wrong. A year into the program I knew it wasn’t the right fit for me.

I had a lot of shame about leaving my doctoral program, but now I know it was absolutely the right decision. I found my calling as an editor, which is my profession to this day. I don’t have to save the world and, frankly, I couldn’t even if I wanted to—and I tried. I wouldn’t trade the years I spent in academia for anything, as I met amazing people and had some incredible experiences. I didn’t fix racism, but I know I was the best example I could be and I’m proud of that—and that’s enough.

I found coping strategies that work for me

In my day-to-day, I’ve had to find ways to best care for my mental health. Here are five things I keep in mind to do just that, and how maybe you can, too.

Affirmations really do work

When I was first told by a therapist that I should do affirmations, I honestly thought the idea was cheesy and likely a waste of time. But once I started actually doing them, I realized that they can be quite powerful. Maybe it’s because speaking them aloud makes them seem more real, or maybe it’s because you have to acknowledge good things about yourself in an honest way, or maybe it’s both. “The language between our ears is powerful stuff,” Young explains. “It’s much healthier for us to navigate the direction of that language on our terms.”

Next time you find yourself feeling less than stellar, think about all of the characteristics you like about yourself or that other people have told you they appreciate about you. Say them out loud—I am fun to be around, I am an engaging conversationalist, I am a caring person—and really allow the compliments to stick. You can start simply by telling yourself that you are worthy of a compliment, that you are worth forgiving, that you are at heart a good person. Trust me, when you do them and mean them, they work.

Remember you’re already enough

Let’s face it, the world can be a huge and intimidating place. And while I do love traveling and exploring exciting places, my life is pretty tame the vast majority of the time. I work from home, I have planned mealtimes, I don’t go out on weeknights, and I don’t have a ton of social engagements. I do things at pretty much the same time every day, and I often eat the same things for breakfast and lunch. I call this “keeping my world small,” which allows me to get through each day without upset and incident.

Just because you have a small life with a regular job and a regular shopping list doesn’t mean that your life lacks meaning. Rather, it allows you to set your intention each day, get through it, and often find yourself enjoying your life. Don’t pressure yourself to write that novel or compose that symphony if you’re not up for those tasks. Be yourself and do the best you can with what you have, and that’s enough.

Exercise has the power to improve your life

I can’t emphasize enough how much exercise has helped me bolster and protect my mental health. I started exercising intentionally over 20 years ago and learned pretty early on how much it can boost my mood, eliminate negative thoughts, quell my anxiety, and allow me to feel the joy of moving my body. It’s not a replacement or substitute for therapy and medication, but as a tool in your mental health care arsenal, it’s very powerful.

Indeed, science has shown us time and time again that exercise is good for both your physical and mental health. Whether you’re taking a walk, working with a trainer, or playing sports with friends, exercise has the power to change your life. I don’t know where I would be without it.

Nature can remind you of the world’s beauty

Making it a point to spend time in nature has helped me cultivate joy and beat back anxiety. When you stop to think about it, sunrises really are beautiful, so I watch them almost every morning. Additionally, having an experience with animals (even your own pets) can be incredibly fulfilling. There really are so many stunning places in the world, even with tragic events happening all the time.

Solid evidence shows that spending time in nature can have a profound and healing impact on mental health. “Regardless of whether we’re walking in the woods, stargazing in a field, climbing a mountain, or floating in the ocean, nature gives us golden opportunities to take a break from the endless chatter of our minds and come home to the peace and quiet outside of it,” Young explains.

Nature has been here longer than we have and will be here when we’re long gone; it is timeless and reminds me how diverse and beautiful Earth is. So if you can, go outside, even if it’s just to a park. You may find that doing so is incredibly healing.

Giving back can help you find good in the world

After the traumatic events of 9/11, I learned firsthand how cruel and callous the world can be. There’s nothing worse than losing someone you love, and when it’s the result of an intentional act (by a stranger no less), it can be pretty difficult to believe that there’s much good out there. Even 20 years later, I sometimes go down the rabbit hole, lamenting about domestic violence statistics or the devastating reality of racial violence—two examples in which innocent people are harmed by malevolent forces, just as my father was on 9/11.

However, a therapist helped me realize that evil in the world doesn’t negate the fact that there are kind souls, so I found ways that I could give back. I became a regular platelet donor, showing that people (in this case me) can do good things for strangers just because they want to. I also volunteer with racial advocacy groups to help elevate the voices of marginalized people. By giving back, I can see the power that goodness has and experience the utter joy of being able to actively do selfless things for others. “When we do something meaningful to help other people, we’re devoting our attention to something outside of ourselves,” Young says. “We find purpose in life through meaning and connection, and service to others rewards us on both of those fronts.”

So give blood, donate to causes you care about, and find the places in your community where you’re needed. I promise it can be transformative—even if you’re not saving the world.

Reflecting on these past two decades, how am I doing now? I’m thriving, though I’m not the same person I was 20 years ago. I’m vulnerable, but I have learned to see that as a strength instead of a weakness. I also have had incredible moments talking with people who have heard about my story and find connection in it. There is a real power and responsibility that I carry within me, as I have been able to share catharsis with many people scarred by the events of 9/11. And I still have my friends from my years in academia, who are from all walks of life—Arab, Muslim, Christian, atheist, you name it. Bonding over our collective humanity has given me hope that we can come together and move ahead. There is life after trauma, and it can be beautiful, even if it’s different from what you could have ever imagined before the worst happened. I’m living proof.