The Pandemic Will Affect Students’ Mental Health for Years to Come. How Schools Can Help

Education Week by Arianna Prothero

March 2021

As COVID-19 vaccines roll out and more schools inch toward fully reopening for in-person instruction, educators and policymakers are rightly focused on getting students caught up academically.

But that will be only half of the battle.

The pandemic, combined with a massive experiment in remote schooling, a racial justice movement stemming from police killings of Black Americans, and economic and political instability will have long-term effects on schoolchildren’s mental health.

For the foreseeable future, educators will have to grapple with a host of additional challenges that will complicate students’ abilities to learn, such as increased anxiety, substance abuse, and hyperactivity—all symptoms of the trauma many students have lived through this past year.

“Right off the bat we know that those stress reactions will make it harder for children to learn,” said Robin Gurwitch, a psychologist and professor at Duke University Medical Center, and a specialist in childhood trauma. “One of the best predictors of how our children are going to do is based on how we’re doing as their parents and caregivers, and the pandemic has not left anyone un-stressed.”

Through her work, Gurwitch has witnessed firsthand the aftermath of mass shootings, natural disasters, and terrorist attacks. She was only a few years into her first job working as a child psychologist in Oklahoma City in 1995 when the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building was bombed, killing 168 people in an act of domestic terrorism.

While this may be the first global pandemic that today’s schools have weathered, there are lessons that educators and policymakers can glean from other major disasters on how students will react and what kind of supports they will need.

Research highlights many possible responses

Research on how children have responded to traumatic events shows that there are myriad ways kids will react—and those reactions may not always be obviously related to the pandemic.

Students may have trouble concentrating or paying attention in class and retaining new information, said Gurwitch. Children’s responses to trauma sometimes look like attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, Gurwitch said, and schools and families might jump to that diagnosis and miss the opportunity to take a trauma-informed approach to addressing the root causes of students’ behavior.

Students may also have trouble with sleep—sleeping too little or too much, said David Bond, the director of behavioral health at Blue Shield of California. Bond was previously a pediatric trauma specialist at the Rady Children’s Hospital of San Diego.

Another big issue for educators to look out for is a rise in substance abuse, in particular vaping. Bond is concerned that stress—and just boredom from being at home all the time—is leading to an increase in e-cigarette use among youth.

“It makes sense,” Bond said. “Because we can’t really go to restaurants, or go to concerts, or football games, … or even go to school, our—especially young—minds are rather understimulated.”

About a year after most schools across the country were shut down in response to the pandemic, large swaths of students are saying that they are already experiencing some of these issues.

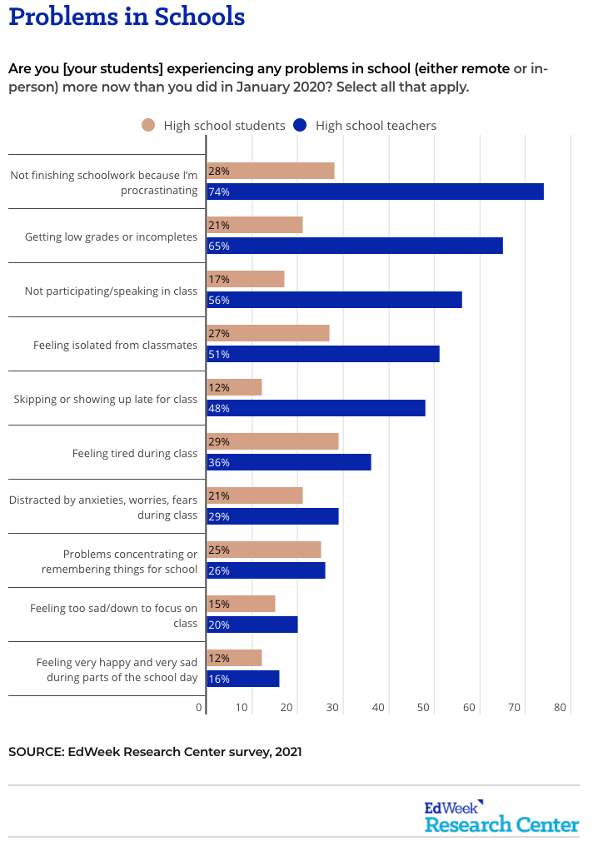

In an EdWeek Research Center survey administered in January and February 2021, high schoolers reported that since the pandemic began, they are getting lower grades and procrastinating more on school assignments. They are distracted by anxiety and having trouble concentrating or remembering things. They are more tired in class and feeling isolated from classmates.

It’s the long haul that has gotten to Joel Castro, an 11th grader at Herbert Hoover High School in San Diego. He has been learning remotely since last March, and he said he is struggling with staying motivated in his classes—something he hears from friends a lot, too.

“Even for someone who is introverted like myself, it’s crazy to me that I’m longing for attention,” he said.

Staying connected with friends without a daily schedule that automatically brings them together has been tough, Castro said. He is not just missing the friends he has at school—he is missing the ones he hasn’t made.

“I feel like this is a crucial time in our development, figuring out what kinds of people we like to hang out with,” he said. “It’s just disappointing.”

High schoolers aren’t the only ones struggling. Erika Brown, a kindergarten teacher in New Orleans, says she can see the effects of the stress of the pandemic—in particular a chaotic school schedule that has bounced between in-person and remote learning—on the little ones as well.

“It is harder to engage them and understand them socially,” she said. “They can’t explain to me why they feel the way they feel, or why the day is just challenging to them. … I do see a difference in how they are responding to school and how they cope throughout the day.”

While it is impossible to put an end-date on when students’ mental health will rebound, say Bond and Gurwitch, educators need to be prepared for those issues to persist for the next several years.

“I do think that kids will settle in, and I don’t think it’s going to be years and years and years,” so long as adults are proactive, said Gurwitch. If a student is struggling emotionally, don’t wait to intervene, she said. “Jump in early.”

What makes the pandemic unique?

While there are parallels between the coronavirus pandemic and other traumatic events, this experience remains unique, said Bond. It’s not a single, terrifying, acute event like a wildfire or the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center.

“Having this level of chronic trauma, I liken it to, if you held a five-pound weight in your hand for a few minutes, no big deal. Your arm can take the stress,” said Bond. “But if you were told you had to hold that five-pound weight in your hand for four hours, that is really daunting. … Something that was a relatively smaller stressor becomes really fatiguing on your body. That’s what chronic stress is like: It’s a weight you can’t put down.”

Teachers also need to be equipped to understand and identify mental health issues in their students, such as through mental health first-aid programs or suicide prevention training, said Bond. Sustaining the necessary support for students’ mental health over the long run will require that educators also take care of themselves and their own mental well-being, and that school and district leaders make that a priority.

It’s also clear that the pandemic hasn’t affected all students equally—and it won’t down the line.

Some children have had a difficult year that doesn’t rise to the level of a traumatic experience, while others have lost financial means and loved ones.

The children that experts are most concerned about are the ones who were already living under highly stressful and traumatic circumstances, such as food insecurity or pervasive neighborhood violence. Those students have fewer reserves to draw on to weather the additional stresses and challenges posed by the pandemic.

COVID-19 isn’t the only thing weighing on young minds, either, said Marleen Wong, a professor at the University of Southern California’s school of social work and a nationally recognized expert on school crisis response.

“I also look at current events and I’m concerned about … the recent political upheaval, the increase in racial tensions,” she said.

Wong, who was formerly the director of mental health services at the Los Angeles Unified School District, said if there were one piece of advice, she would give to schools now, it would be to start formalized assessments of students’ mental health to understand exactly what they have been going through.

“We also know that pre-existing conditions and pre-existing challenges are part of the assessment that needs to take place,” she said. “So, of course, in situations in communities of poverty, in communities where there are large numbers of folks who have been exposed to crime or violence, especially among families of color, you really need to be concerned about how they have been affected most.”

However, even for students experiencing similar circumstances, the impacts can be uneven.

“One thing I have learned, trauma affects people differently,” said Jake Heibel, the principal at Great Mills High School in Great Mills, M.

In 2018, one of Great Mills’ students shot and killed his girlfriend at school, before fatally shooting himself.

“We are nearing the three-year mark,” said Heibel, and the freshmen on that day are now seniors, poised to graduate. “Some people dealt with it early on, and others struggle with it still today.”

That’s the case for both students and staff, he said, and balancing the differences has been a challenge. He admitted it can also be difficult sometimes to distinguish signs that students are truly struggling from more-typical teenage emotions.

“Being a teenager in many ways really does stink, and there are ups and downs, and our counseling staff tried to determine is this related to the shooting or just life in general,” he said.

Another lesson from the shooting, said Heibel, was the importance of meaningful relationships between school staff and students in helping students overcome trauma.

In response to the pandemic, Heibel recently created a mentoring program where participating teachers, who are matched with three students each, are tasked with monitoring students and how they’re coping.

This has been a ‘year of heartaches’

Castro, the San Diego student, said he thinks it’s going to be a long climb out of the pandemic, and that it will affect his emotions, and those of his friends, for a long time yet.

“The whole year has been a lot of disappointments and heartaches,” he said. “Especially for youth, who are more easily shaped by events than adults.”

But he is also optimistic. Hitting the one-year mark of the pandemic shuttering schools was motivating for him, he said.

“I guess that marker kind of serves as motivation,” Castro said. “I’ve made it this far, and things are starting to look up because there’s talk of maybe reopening schools in a few months. Vaccines are rolling out. It’s starting to feel like maybe we’re approaching the end of this.”

But the aftershocks of a traumatic event can shake students’ schooling for years to come. Brown, the New Orleans teacher, knows from experience. She was a 5th grader when Hurricane Katrina hit. Her family evacuated to Houston, not returning to New Orleans for another two years. Shortly after Brown moved back and started 7th grade in a city that was still struggling to rebuild after the storm, her mother died.

Brown said there are things she still grapples with as an adult that she traces back to that time.

“It’s hard for me to adapt to change—I think that’s because of Katrina and losing my mom. I need structure,” she said.

Brown says she has been shaped by both the storm and the teachers who invested in her, changing her life trajectory.

There was a young 11th grade teacher placed in her school through Teach for America who pushed Brown to go to college and inspired her to join TFA and become a teacher herself.

If her experiences as a 7th grader offer her adult self any teaching advice, said Brown, it’s this: “To be patient and to provide as much consistency and stability as possible. Those are the things that our kids can’t articulate that they need, but they need that, especially right now as things are ever-fluctuating.”

For example, Brown said, she sets aside time every morning to just chat with her class—whether they are learning in-person or virtually. They talk about their days, or she poses a question to the students. It’s something she can control, and it gives her students that consistency.

“This is another thing I would tell teachers— is just to really see your students,” she said. “Let them feel heard and seen.”