Loneliness, Anxiety, and Loss: the Covid Pandemic’s Terrible Toll on Kids

April 9, 2021, The Wall Street Journal

By Andrea Petersen, Maria Alejandra Cardona

A year of school shutdowns and family trauma leads to social isolation, stress, and mental health issues

When Victoria Vial’s Miami middle school shut down last spring and her classes went online, it felt like the beginning of an adventure. “I was in my pajamas, sitting in my comfy chair,” the 13-year-old recalled. “I was texting my friends during class.”

Then she received her academic progress report. An A and B student before the pandemic, she was failing three classes. The academic slide left her mother, Carola Mengolini, in tears. She insisted her daughter create to-do lists and moved the girl’s workspace into the guest bedroom to pull up her grades.

Over the summer, Victoria’s tennis and theater camps were canceled. Her family postponed a planned trip to Argentina to visit her extended family.

She formed a pandemic pod with five close friends, but the girls bickered. Sub cliques formed, and Victoria and her best friend found themselves excluded. The pod fell apart.

The return of in-person schooling last fall brought some relief, but with some of her classmates still at home, teachers had to shift their attention between in-person kids and those online, leaving students feeling disorganized and behind.

The biggest blow came in December when Victoria’s 78-year-old grandfather died of Covid-19. Her mother flew to Argentina for six weeks to help her grandmother. Her father, grief-stricken and withdrawn, had little energy to cook or clean. Christmas came and went without the usual celebratory meals and piles of presents.

“It was super, super hard,” says Victoria. “I didn’t know how to feel. All of the people I look up to, they are all, like, breaking down.”

She grew anxious about going to school—afraid she would catch the virus and spread it to her parents. Some classmates didn’t believe Covid was real, she said, and some wore their masks down below their chins or dangled them from their ears. Students talked and laughed in clumps, without social distancing. Her grandfather’s death loomed large. “They don’t understand how quick it all can just change everyone’s lives,” she says.

She turned to social media for solace and to stave off boredom. She gave herself makeovers and posted the results on Tok-Tok. She cut her bangs, then added a pink streak to her hair. She added four new ear piercings with a safety pin. She shaved part of her head.

As the months piled up, she found it hard to stay motivated to do her schoolwork. Her grades have started falling again. “Every day is the exact same,” she says. “You kind of feel like, what’s the point?”

Multiple blows

Rarely have America’s children suffered so many blows, and all at once, as during the pandemic’s lost year.

The crisis has hit children on multiple fronts. Many have experienced social isolation during lockdowns, family stress, a breakdown of routine, and anxiety about the virus. School closures, remote teaching, and learning interruptions have set back many at school. Some parents have had job and income losses, creating financial instability—and exacerbating parental stress. Thousands of children have lost a parent or grandparent to the disease.

It is unusual to have so many challenges at once, and for so long. As vaccinations rise and restrictions are lifted, the looming question for this generation is: What will the long-term effects of the lost year be?

That question will take years to answer. But there are clues in what we know from previous disasters and emerging research on the pandemic. Psychologists and researchers say that the more major traumas and stressful situations a child experiences, the deeper the impact will be. Children with pre-existing problems such as anxiety and depression or learning disabilities likely face greater challenges. And children living in poverty may have an especially difficult time.

Harvard University researchers who have been following 224 children ages 7 to 15 found that about two-thirds of them had clinically significant symptoms of anxiety and depression, and the same number had behavioral problems such as hyperactivity and inattention, between November 2020 and January 2021. That is a huge jump from the 30% with anxiety and depression symptoms and the 20% with behavioral problems before the pandemic. Symptoms were more common in children who had experiences such as having a family member hospitalized or dying from Covid, or a parent losing a job.

The biggest driver of child well-being during Covid is how parents are functioning, according to a survey of nearly 500 parents with children ages 8 to 17, conducted by Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.

“There’s more family conflict because of the pandemic. That is leading to stress, acting out, increased suicidal thoughts in the kids,” says David Axelson, chief of psychiatry at Nationwide Children’s. Dr. Axelson says visits to his hospital’s psychiatric crisis department, for emergencies including suicidal thoughts, aggression, and psychosis, were up 14% this fall and winter from a year earlier.

Particularly delicate are the years from 8 to 14. The years around puberty are ones of greater neuroplasticity when the brain is particularly sensitive to external events and learning experiences. It is when children begin to form their identities and start to separate from their parents. It is also when mental-health issues such as depression and eating disorders can emerge.

“This is a pivotal time,” says Ronald E. Dahl, director of the Institute of Human Development at the University of California, Berkeley. “The capacity for high-intensity emotional learning is enhanced. You’re thinking for yourself and developing certain kinds of proclivities and mindsets.”

Both positive and negative experiences, particularly social ones, land harder. And they start to shape children’s trajectories. Children who struggle with schoolwork and don’t get positive feedback may start to feel that school is “not you,” says Dr. Dahl. They may stop trying academically, which only reinforces that perception. “You start constraining your pathways, beginning to actively select these paths and avoiding other ones,” he says.

The good news is that in children this age, troubling trajectories can be relatively easily reversed with positive experiences and by supporting kids through challenges, says Dr. Dahl. These kids also are generally more receptive to guidance from caring adults compared with older adolescents. Psychologists and pediatricians say the majority of children will likely bounce back from the pandemic’s challenges, but some might struggle for years.

Academic woes

For much of the academic year, many students were stuck at home with remote instruction. Evidence is mounting their learning suffered.

In the fall of 2020, math performance among third- to eighth-graders was 5 to 10 percentile points lower than it was in the fall of 2019, according to a report by the Brookings Institution. An analysis by McKinsey & Co. estimates that Covid-related learning losses among kindergarten to 12th-grade students will reduce their lifetime earnings by between $61,000 and $82,000. And those numbers assumed that students would largely be learning in person by January 2021.

Until this school year, 10-year-old Jonathan Giden and his brother Marcus, 12, were A and B students. During the months that South Bend, Ind.’s schools were solely online, their grades plummeted. Since Jonathan and Marcus’s parents usually can’t work at home, the brothers were often alone during the day. The Wi-Fi could be spotty. Jonathan sometimes didn’t understand assignments. He would ask Marcus for help, pulling the older boy away from his own studies.

The lure of video games, YouTube and television often won out over schoolwork. “When I see new things, I like to try it out, and when that new thing is fun, I just like to stay on it and I forget what I’m supposed to be doing,” Jonathan says.

The boys’ grades rebounded somewhat after their local Boys & Girls Club reopened and the brothers began going there during the school day. The center’s employees helped them keep track of their assignments and troubleshoot technology problems. Now that South Bend public schools are doing a hybrid of in-person and remote instruction, Marcus is in school two days a week and Jonathan is in school four.

Their mother, LaToya Giden, worries that her sons’ struggles with remote learning will have serious long-term consequences. “What skills are they lacking now? How low did their reading go? How low did their math go?” asks Ms. Giden, 42, a social worker.

Jonathan, who is in fourth grade, is slated to take a crucial test this fall, the results of which will largely determine whether he will land a spot at the high-performing public middle school where Marcus is now. Next year, Marcus, who is in seventh grade, will be applying to high school. The school Ms. Giden and her husband, Marcus Giden Sr., want him to attend requires excellent grades.

Ms. Giden sees these hoped-for schools as critical to her sons’ futures, steppingstones that will lead to good colleges and successful careers. She worries that the academic setbacks caused by school closures will hurt her boys’ chances of getting in.

Stress factors

Psychologists and pediatricians say they have seen a rise in parental abuse and neglect, substance abuse, mental illness and divorce during the pandemic. Past research has shown that exposure to a high number of such issues—what researchers call Adverse Childhood Experiences or ACEs—can cause changes in how children’s bodies respond to stress, which can damage the developing brain and immune system. Exposure is associated with an increased risk of a host of health issues, including depression, diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and substance abuse.

“We see intimate-partner violence increasing, mental health deteriorating among adults, increasing substance dependence. All of those means increasing ACEs for the kids,” says Nadine Burke Harris, a pediatrician and surgeon general of California.

Scientists have found that children with post-traumatic stress symptoms tied to these experiences have changes in brain regions including the amygdala, which is involved in processing fear and emotion; the hippocampus, which is involved in memory; and the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in executive functioning.

Such brain changes, if “not attended to, are going to lead to emotional, cognitive, academic issues later in life,” says Victor G. Carrion, director of the Early Life Stress and Resilience Program at Stanford University.

“If a parent is emotionally unavailable or in distress themselves, they will be less effective parents,” says Arwa Nasir, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

For 9-year-old Nelle Thin Elk, the pandemic has brought a torrent of tragedy. Last summer, her mother, Ivette Shupla, was laid off from her job in Phoenix. Nelle’s father, who lost his job before the pandemic, began drinking heavily, Ms. Shupla says, and started physically abusing her. In September, he killed himself.

“I’ve talked with her about death,” says Ms. Shupla. “She knows that I get sad. She knows how I grieve.”

After her father’s funeral, the third-grader stopped logging onto her remote classes. “After my dad passed away, I was too sad to stay on my Zoom,” Nelle says.

In December, Ms. Shupla and her daughter, who are Native American, moved from Phoenix to the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota, where Ms. Shupla was offered a job at a nonprofit—and where she has family who could house them while they looked for a place of their own.

Not long after the move, Covid swept through the family. Nelle and her mother had mild symptoms. Nelle’s great-grandfather died from the virus. So did Ms. Shupla’s aunt and cousin. Ms. Shupla said Nelle and her older brother, who is 11, have been coping with all the loss by leaning on one another, and that her daughter still finds comfort in favorite activities such as drawing.

The pandemic has fueled poverty and difficulties affording food and housing, which are associated with negative outcomes, including poor school performance and obesity. In March 2020, 38% of families skipped meals or didn’t have enough money to buy nutritious food, according to a nationwide survey conducted by researchers at the University of Arkansas. In 2019, 10.5% of households couldn’t buy enough food or were unsure if they would be able to do so at some point during the year, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Mental toll

In a June 2020 survey of 1,011 U.S. parents published in the journal Pediatrics, 14% said their children’s behavioral health had worsened since March. About 23% of elementary school students in Hubei province in China had symptoms of depression and 19% had anxiety symptoms after more than a month of home confinement last year during the region’s coronavirus outbreak, according to a survey of 1,784 children published in April 2020 in JAMA Pediatrics.

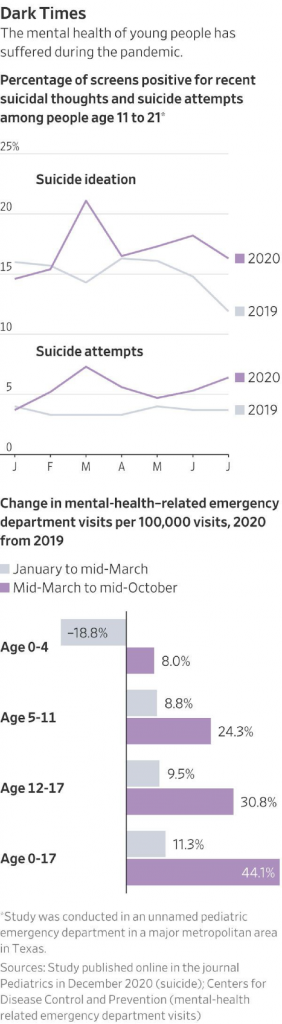

And while fewer children are being seen in hospital emergency rooms during the pandemic, a greater share of visits are for mental-health reasons. Between mid-March and mid-October 2020, the number of mental-health-related ER visits per 100,000 total visits rose from the year-earlier period by 24% for 5- to 11-year-olds and by 31% for 12- to 17-year-olds, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Those increases are on top of the already rising incidences of anxiety, depression, and suicide among children and teens before the pandemic.

A fourth of parents of children attending school remotely said their kids’ mental or emotional health worsened, compared with 16% whose kids were attending in person only, according to a CDC survey of more than 1,200 parents with children ages 5 to 12, conducted in October and November 2020.

Mary Alvord, a psychologist in Chevy Chase, Md., says she is seeing two main issues in her practice: anxiety about schoolwork and sadness over not being able to see friends.

Doctors say they also are seeing more children with eating disorders. The Center of Excellence in Eating and Weight Disorders at Mount Sinai Health System in New York has received about 105 calls a week over the past year, up from about 30 before the pandemic. The majority were from families with children ages 8 to 14 when disorders like anorexia often emerge, says Tom Hildebrandt, the center’s chief.

Some children are restricting what they eat and losing weight in an attempt to deal with the stress and uncertainty of the pandemic, Dr. Hildebrandt says. Others are bingeing because of “lack of stimulation or boredom,” he says.

Michaela Voss, medical director of the eating disorders center at Children’s Mercy in Kansas City, says hospital admissions for children with eating disorders have risen substantially during the pandemic. With many schools shut down and organized sports canceled, some children felt “there was nothing else to do but exercise and stare at their bodies in mirrors,” Dr. Voss says.

Julie Balaban, a child and adolescent psychiatrist at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in New Hampshire, says she is seeing more children come to the emergency room with dangerously low heart rates or fainting because they are eating so little.

The children most at risk for mental health problems are those who have a history of them, says Rebecca Rialon Berry, a clinical associate professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at NYU Langone Health in New York. Children who have an existing condition, such as anxiety or depression, are at risk for worsening symptoms.

Miranda Souki, 13, saw a therapist for school-related anxiety and sleep problems three years ago. She had been doing well since then, until the pandemic. The eighth-grader in South Miami, Fla., became terrified of contracting Covid and passing it to her parents and grandparents. “I don’t want it to be my fault” if they get sick, she says.

Miranda tried to avoid any news of Covid and would beg to skip Zoom calls with friends and family because she knew the subject would come up.

On Mother’s Day, the family gathered for the first time since the state’s lockdown eased for a celebration at Miranda’s grandparents’ house—a Covid-safe meetup outside, socially distanced and with masks. Miranda had a panic attack.

“Boom. It was this flooding somewhere near my heart, lungs, rib cage,” she recalls. “It was very much, ‘I don’t want to be here.’ ” She started therapy again in June, which she says helped her cope with anxiety.

Miranda has been attending school full-time in person since the fall. She has created an elaborate safety regimen. She wears two masks and a face shield and carries a bottle of Lysol, hand sanitizer, and a pack of wipes to clean her hands and everything she touches. She hangs back after classes and waits for the hallways to empty out before she dashes to her next subject. Still, the worries come—and they are worse at night.

“I’ll be lying awake, and I see images of my day,” she explains. “That my friend handed me something and I put hand sanitizer on it. But did I wash my arm? It might have gotten on your arm, and you rubbed your arm on your bed, and now your bed has Covid.”

In studies on the aftermaths of other disasters—hurricanes, fires, the 9/11 terrorist attacks—from 30% to half of children have some initial negative reaction, including symptoms of anxiety, depression, and overall distress, but bounce back. Another one-third are just fine from the start.

The remaining 15% to 30% have persistent problems. They have physical symptoms like headaches and fatigue, as well as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress symptoms. They struggle in school and might have long-term learning and memory issues. Children who have pre-existing mental health conditions, who have additional stresses such as poverty or abuse, or have the most direct exposure to the disaster—seeing a tree fall on their home, for example—are most at risk for such long-term problems.

Scientists say they expect the pandemic to cause deeper and more chronic suffering for more children than most natural disasters. “What makes the pandemic different is how long it has been going on and how many people are affected,” says Betty S. Lai, an assistant professor of counseling psychology at Boston College.

Social anxieties

After the pandemic wanes, many children, especially those who are socially anxious or have learning disabilities, may face a bumpy re-entry period trying to catch up in school and dust off dormant social skills. “As expectations increase for them being out in the world, I expect to see a group of kids that really struggles with it,” says Jill Ehrenreich-May, a professor of psychology at the University of Miami.

Mihika Deshmukh, 13, says she feels that “it’s been a lot harder to make friends and talk to new people.” The eighth-grader in Pleasanton, Calif., has been attending school remotely since March 2020. During the entire pandemic school year, she has met up with a friend in person just once.

She and her friends had been connecting via FaceTime and Zoom regularly, but in recent months those calls have dwindled. “I feel like a lot of us drifted apart,” she says. “It has set in that I’m alone.”

She feels sad and lonely at times. When she does connect with friends online now, Mihika says, they prefer to share their Spotify playlists and listen to music or do their homework silently rather than talk about their problems. “Even if you’re not talking, it feels like you’re with someone,” she says.

Emerging research is identifying strategies that may help children be more resilient in the face of the pandemic. The study in progress at Harvard of children and teens has found that those who had structured routines, got more exercise, and had less screen time had fewer behavior problems and fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression.

“Routine and structure are really important for helping kids regulate their emotions and respond to all the other chaos that’s around,” says Katie A. McLaughlin, an associate professor of psychology at Harvard who is leading the study.

Children 12 and younger who had at least some in-person time with peers—in a Covid-pod, for example—also did better. The same wasn’t true for teens, however.

Psychologists recommend that parents help their children find activities that give them a sense of purpose and help them set related goals—whether that be writing a graphic novel or learning to bake bread. Helping others can boost mood, as can adequate sleep.

For 12-year-old Cole Barker of Chillicothe, Ohio, the pandemic has meant a canceled Little League season and no 4-H summer camp. His parents tested positive for Covid-19 in December. “I was kind of scared,” he says. “My dad was in the basement. I was scared that he wouldn’t be able to come out of the basement.” His parents both recovered, though his mother had lingering fatigue for months.

What kept Cole going, says his father, Jamie, was the routine of feeding, brushing, and walking the two pigs, Tex and Nancy, that Cole raised for 4-H. “I was just thinking I’ve got to keep doing what I love,” Cole says.

Victoria, the Miami middle-schooler, also can point to some high points during her otherwise tough year. Last summer, she and her friends created an arts-and-crafts camp for some younger children in their neighborhood. They named it “Camp Quaranteam” and earned $3,000.

Another escape has been listening to her favorite songs by artists like Drake, Kanye West, and Post Malone. She snuggles with her kitten, George, a former stray her parents allowed her to keep because they thought a pet would help.

She thinks about all the other kids in the world who are living through this time, too. It helps her feel less alone. And Victoria has big plans for when the pandemic ends.

“I want to go to a concert with my friends so badly,” she says. “I see me and my friends yelling the lyrics at each other and screaming the artist’s name and just jumping up and down.”

— Design and development by Jessica Kuronen and Jason French.