Opioid overdose deaths rise among Blacks; one Birmingham mother an inspiring model for recovery

AL News Updated for July 2021

With opioid overdose deaths among Blacks on the rise, Kim, 36, wants to be a model for others stuck in the depths of addiction.

She doesn’t remember his name. Kim Davis can’t recall the name of the guy who saved her life. The guy who found her after she snorted a half gram of heroin off her pinky nail—just like white people do it, she thought. Heroin cut with fentanyl, a potent, too-often deadly opioid.

She doesn’t remember the name of the guy who likely heard her emit the death growl, she calls it. The sound addicts make when they’re OD’ing. He heard it and took action and put her in the shower on that night in 2016.

Davis, a Birmingham native, laughs about it now—right after shedding tears when recalling the deepest depths of her arduous journey, the “really bad” places. Places darkened by drug use (selling, too, which she began at 14 years old), by promiscuity, by cancer, by imprisonment, by two overdoses (the second in 2018), by mental and spiritual defects from which she could have easily not risen.

Davis is far from those places now, thankfully. She’s 36 years old, a committed mother of six (three by birth, three soon-to-be stepchildren), a hairstylist, and an assistant manager at an Irondale salon.

She is engaged to the love of her life. “He knows everything I’ve been through,” Davis says. “When I tell him my stories, you know how people’s voice changes when they hear something really crazy?—his doesn’t change at all. No judgment.”

Also, Davis says she has not used drugs since December 2020 and is a model patient in UAB Medicine’s Beacon Recovery Integrated Healthcare program.

“I just want to be an example,” Davis says. “I am a walking testimony. I’m an open book.”

NO LONGER A “WHITE” ADDICTION

Not long ago, she would have been an anomaly—an African American fighting opioid addiction and suffering an overdose related to Fentanyl. No more.

The opioid has long been used in heroin (added to heroin to increase its potency) but in recent years it is increasingly found in other drugs, including cocaine and methamphetamine. It’s also sold in counterfeit pills and often mistaken for cocaine when crushed.

The result: opioid-related overdose deaths are no longer a “white” thing.

In Jefferson County, fentanyl-related overdose death among Blacks increased 93% between 2019 (58) and 2020 (112), according to data provided by the Jefferson County Department of Public Health.

Statewide, overdose deaths among African Americans also soared during that period—from 129 (“Black and other” is how the state classifies non-white deaths) in 2019 to 219 in 2020, according to data from the Alabama Department of Public Health, a 60% increase. (Overdose deaths among whites rose slightly, from 639 in 2019 to 662 in 2020.)

“Fentanyl has been in the heroin supply for several years when the typical demographic profile of an overdose victim was a white male in 30s,” says Dr. F. Darlene Traffanstedt, Medical Director, Adult Health & Family Planning at JCDH. “When it entered methamphetamine and cocaine, it broadened the demographic of individuals at risk, which is most troubling among African American males and females.”

Nationally, as well. The largest spikes in overdose deaths across the U.S. in 2020 was among Blacks (50.3%) and Latinos (49.7%), according to researchers from the University of California, Los Angeles, who studied data from emergency medical calls and compared overdoes deaths during the pandemic to 2018-2019.

State health officials initially hoped to attribute the spike to the pandemic, which impacted people in myriad unhealthy ways.

“In our minds, we thought when the pandemic began to subside, things would get better,” says Traffanstedt, “but ’21 is off to a worse start than 2020.”

A lot worse: Fentanyl-related overdose deaths in Jefferson County in the first quarter of this year were up 126% over the same period last year, according to the JCDH—from 34 to 77.

DECISIONS WITH CONSEQUENCES

Davis’ journey is not an anomaly, either. Like so many southerners, she grew up in the church. “I have a good relationship with God,” she frequently says. Her family lived in East Lake until their mother, a nurse, moved to Huntsville when Davis was in third grade. They returned to Birmingham when Davis was an 8th grader; she enrolled at Huffman Middle School.

Davis had two younger siblings and a sister seven years older. For her and the younger ones, moving from north Alabama to Birmingham was a “culture shock,” she says. “I didn’t grow up rich, but we weren’t poor, either. We went from wearing penny loafers and Keds to [folks wearing] Jordans and Tommy Hilfiger. My mom didn’t do all that name-brand stuff.”

In the single-parent household, Davis felt like a “role model” for her young brother and sister, a caretaker who would do anything to support them. Even sell drugs. “I was selling crack and weed at 14,” she says, “to pay for stuff they wanted.”

It’s easy to look back and condemn the decision and the future ones that spiraled Davis into many depths; it’s harder to consider the conditions that contributed to them—conditions that still lead young people to decisions they’ll likely someday regret. If they live to do so.

At 15, Davis was pregnant. She dropped out of 11th grade, homeschooled as much as she could before attending cosmetology school.

At 18, she began drinking and using cocaine and taking pills, she says. She was also an exotic dancer. “I was working white clubs, then started working in a Black club and saw people pimpin’ and doin’ cocaine. It exposed me to the game.”

A game that really isn’t one, of course, a game that drags too many deeper into depths. Depths, though, from which God may still lift you.

In 2008, in her early 20s, Davis was dancing on a stage in Miami, “when God clearly said, ‘This ain’t it,’” Davis recalls. “I walked off the stage, called my mom, and said, ‘I don’t want to do this no more.’ She told me to go straight to the airport and got me home.”

Davis says her mother (she did not want to provide the names of any family members, to preserve their privacy) supported her positive decisions but relied on her faith to absorb the blows of her daughter’s negative decisions. “When I was not doing right and living crazy, she stated on her knees and kept me covered in prayer. She did have to use tough love on me few times.”

CANCER CHANGES THE JOURNEY

In 2011, Davis began to feel pain in her stomach. In March 2012, she learned she had stomach cancer. “That was the start of my journey with pain pills,” she says.

Davis was cleared to stop cancer treatment in May 2013, but it returned in 2014. This time, it was found in seven different places in her body, ultimately requiring 13 surgeries, she says.

She didn’t know if she could beat it but knew she was in pain. Living in Huntsville again, a doctor there prescribed fentanyl patches. Later, though, the doctor was busted and shut down.

As too often happens among young Black women, Black girls, Davis’s path was further detoured by a man. A man who was selling drugs, and who took advantage of her deep need to ease the pain—with powdered fentanyl and “Mollys” (Ecstasy).

“I was dating a guy who said could get the powder form off the street,” she says. “It was the first time I dealt with withdrawals, so I took it and started feeling the high. I was overdoing it and liked it. That’s how it got crazy, buying it off the streets. I could not control it.”

Using and selling is a dangerous elixir. “I went crazy, doing drugs,” she says. “I started slipping and catching charges,” she says.

She left her home in Madison County one evening, got pulled over, with drugs in the car—cocaine, and Mollys. She was not the primary target, so was able to plea to possession of controlled substances and get probation. That was 2012.

Still, she stayed in the game. Kept using. At one juncture, Davis had a $400-per-day addiction. “With the help of my baby’s daddy, I was able to ween myself down to half-gram a day, which was really good.”

Until it wasn’t. Until a car she was riding in got pulled over in Limestone County in 2017, with drugs in the car again, and a gun. Knowing she was on probation in Madison County, Davis fled.

To Florida.

There, Davis began “doing good in life”. She found a job as a security officer working overnights in an upscale neighborhood, was making a “good money” and started living a whole new life.”

“I forgot I was on the run,” she says.

On August 22, 2019, on the way to her shift, Davis was pulled over because, he later said, she pulled in front of him. Yeah, that’s what he said.

Per protocol, the officer ran her name and learned of the warrant out for her for the gun and drug charges. On September 11, she was extradited to Madison County and ultimately incarcerated at Julia Tutweiler. Alabama’s only prison for women.

INCARCERATION LEADS TO FREEDOM

“Doing prison saved my life.” Davis remembers that.

Prison is where she thought she would die high and, well, see above for the rest. There, she got into three fights, was sent to lockup, and just started praying.

“I have a good relationship with God,” she reminded me again. “I was just praying to get out of lockup. He touched me and changed me all the way. I began wanting to be different.”

She also prayed for God to remove “certain people” from her life, including the man she has been seeing in Florida. A man who sold drugs. They were still “together” while Davis was imprisoned, but “I didn’t want to be in the same toxic relationship.”

Davis was released on July 7, 2020

“When I got out, I knew I wanted to commit to change,” she says. “I wanted a whole new start.”

The man to whom she will soon be married was someone she had known for years but was disconnected.

“I was praying for God to bring me back to him.”

THE STORY OF TOO MANY

Davis enrolled in Beacon this past January. What she found motivated her to stay sober, she says, to share the full realities of the depths of addiction. Of withdrawal.

Your pain tolerance isn’t high anymore because the drugs kill your senses. Fentanyl has no smell, no taste so you don’t know how strong it is. Addiction happens because the habit gets out of control. The more you do, the higher your tolerance gets.”

While she was imprisoned, Davis says four friends died from overdoses.

“Four girls I used to hang out with,” she says. “One was pregnant. When you don’t do it for a while your tolerance is back to zero. A lot of ODs happen because you think you can do it the same way you used to. If you snort a point (amount), your body can’t handle that whole point no more.”

She also knows of the external pressures that still entice too many.

“In Birmingham, Brighton, we have areas polluted with heroin, pain pills,” she says. “You just pick up the dope and go.

“That is the story of a lot of people”

“SHE CAN DO IT”

Davis was already at Beacon when Dr. Bradford Davis (no relation) arrived this past January. He worried about her then. “I felt she had a lot going on with addiction treatment and other social stresses, new housing, it was a lot to face for anyone,” he says. “It’s hard to put your basic needs on hold. I was concerned about her ability to do that – as I am with all patients.

She “blossomed,” though, he says. “In groups, she has been an advocate for others.”

Davis says she wants to become a peer counselor and Dr. Davis sees no reason why she cannot.

“I know she can do it,” he says.

“It’s really easy for people who aren’t in recovery or not facing addition to label someone,” he adds. “To dehumanize a person who at the root of this all has complicated issues and faced depression and made choices that are not healthy all the time.”

“When I was running the street, Not only was I bound unwillingly, I wanted to be there. I was okay the way I was. I didn’t care about having no man. But I never was not a good mom. I never looked like I used drugs.”

“At the core of every person with addiction, there is a person struggling and trying to make themselves better.”

NEED FOR NARCAN

“Damn, if I can make it, anybody can make it,” Davis says. “All you have to do is want it and stick to a plan. Why not use that for the good people who know me and know what been through?”

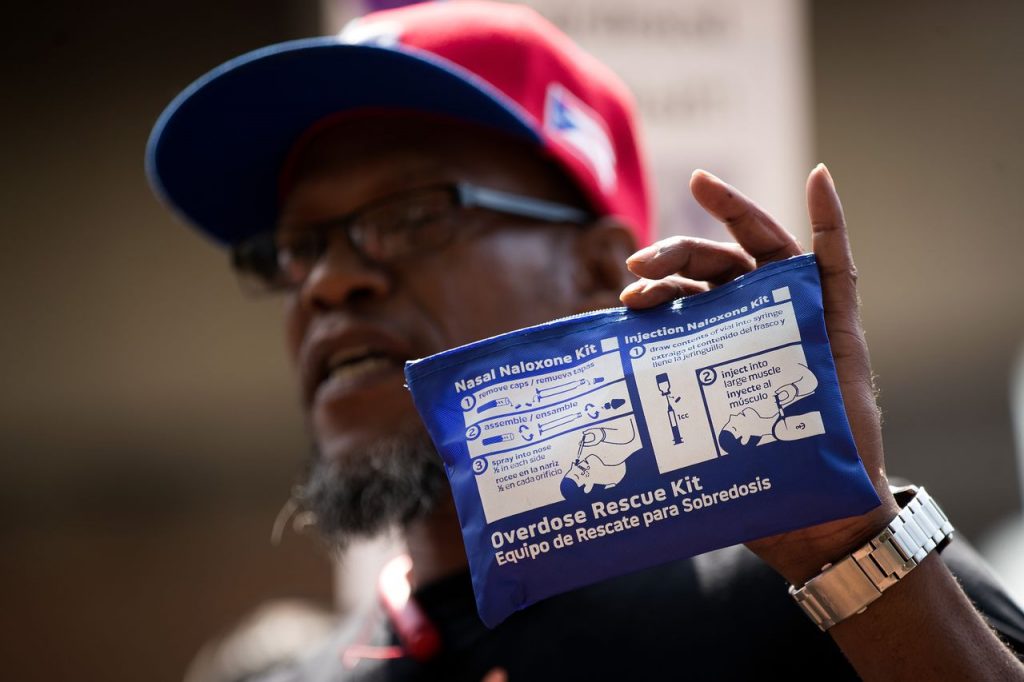

Davis is an advocate for Narcan kits, which contain the medication that can quickly reverse the effects of an opioid overdose and restore breathing in minutes.

“A friend died a month ago,” she says. “Our families went to church together, if they would have just had a Narcan kit.”

On her oldest son’s birthday, his father died of an overdose. “He was with a friend,” Davis says. “He OD’d and she left him. He died on a Sunday, they found him on Tuesday. He was never really a good dad, but he was trying to build his son’s life. We were robbed of that. If she had helped or had Narcan he would be here.”

“Educate yourself and about the symptoms of overdosing, about breathing, behavior,” she adds. “If they look like tired, they’re not tired, they are ODing. If they can’t keep their eyes open, if they’re breathing deep and low—if they’re doing the death growl, they’re ODing”

Narcan kits are free, Davis emphasizes.

“I have one in my car, in my room,” she says. “I don’t plan on ODing, I won’t use now. I won’t even allow doctors to give me narcotics.”

One evening earlier this year, while she was at a Waffle House, Davis saw a couple on a nearby car. They were nodding out, familiarly so. She was not close enough to hear the death growl but knew the signs all too well. She grabbed the Narcan kit in her car and knocked on their window.

“I’m not trying to bother you,” she said, “but take this.”

I wonder if they’ll remember her name.